Sinopsis:

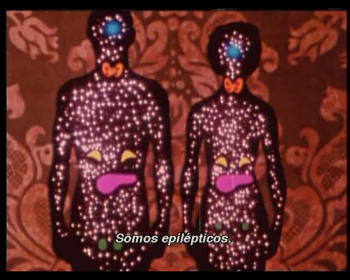

- Un experimento en el que la narración está construida casi en su totalidad por fragmentos de materiales fílmicos de diversa procedencia, kinescopados de programas científicos de los 50/60, anuncios, material educativo, películas comerciales, documentales... Con todo este arrebatador material, Baldwin teje una trama (algo confusa y a veces demasiado sumisa al material disponible) en la que narra la lucha cruenta acaecida en los siglos XX y XXI (y lo que nos queda) por el control de los media.

Redacción de Miradas, en "Para presentar a Craig Baldwin", escribió:No hay dudas de que el realizador estadounidense Craig Baldwin (nacido en Oakland, California, en 1952) se encuentra entre las figuras más destacadas del cine experimental contemporáneo, en particular entre aquellos artistas que realizan su obra dentro de los parámetros del found footage (metraje encontrado por casualidad). Autor de un cine marcadamente politizado, donde la denuncia va de la mano con una muy ácida ironía, el cine de Baldwin también destaca por la maestría con la cual realiza un trabajo de montaje que habitualmente subvierte el sentido original de las imágenes que utiliza.

Egresado de la San Francisco State University, en 1986, Baldwin trabajó allí bajo la supervisión del afamado realizador experimental Bruce Conner, aunque confiesa que sus dos más poderosas influencias son las del documentalista Emile de Antonio y del politólogo y analista de los medios Noam Chomsky. Además de ello, reconoce tener deudas con el movimiento Beat estadounidense y, ya desde un punto de vista quizás más filosófico, con el Movimiento Internacional Situacionista, que dirigiera Guy Debord. Aunque su primera película fue "Wild Gunman" (1968), no es sino hasta "Flick Skin" (1977) que Baldwin revela su inclinación por la manipulación de imágenes tomadas del archivo de la cultura popular y masiva. Por aquella época, mientras vivía encima de un teatro dedicado a la proyección de películas porno, Baldwin se dedicó a reunir trozos de película desechados por los proyeccionistas y que él recogía en los alrededores del teatro. En su trabajo como promotor destacan iniciativas como Other Cinema, programa de proyecciones que promueve el trabajo de cineastas que trabajan en el estilo del denominado "cine pobre", y Other Cinema Digital, agrupación dedicada a promover el trabajo de cineastas experimentales, underground e independientes. Sus obras más conocidas son "Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America" (1991), obra que le mereció ser ganador del premio Goldie otorgado por el diario San Francisco Bay Guardian, "Sonic Outlaws" (1995) y "Spectres of the Spectrum" (1999).

Craig Baldwin sobre sí mismo escribió:«Voy obviamente a la biblioteca, leo libros. Mi trabajo, como dije, le debe mucho al documental, al documental de compilación. La compilación documental tiene una tradición periodística, hay investigación, se escribe un guión. El problema principal es que las imágenes sólo ilustran lo que está en el guión. Es como un artículo y puede estar cercano a mi visión de la historia, pero no hay sorpresas para el espectador. Se dice algo, en términos de texto o lenguaje, y luego se ve una imagen de ese algo. Es una relación de uno a uno. Eso no abre el formato del documental, no le otorga más perspectiva, no hay crítica, no hay reflexión. Tiene cero sentido del humor, no nos hace pensar en algo que vaya más allá, no se relaciona conmigo como individuo o hacia ti como espectador. Muchas decisiones políticas no son hechas por cuánta gente votó o por la cantidad de armas que se mandaron a Irak, sino por ideología, por cómo la gente crea imágenes de cosas en sus mentes. Mi crítica va por el lado de la imaginería, la deconstrucción de imágenes y cómo las imágenes mismas ya están cargadas, preñadas de significado. Cuando tomo dos imágenes que no están relacionadas y las pongo juntas, se produce calor o electricidad. Las imágenes se quiebran y fragmentan y, tomando el modelo del uranio, se dividen. Así vemos de qué están hechas. Este un proceso analítico. De análisis, porque fragmenta las imágenes para ver los gestos, ya sea de la historia del cine, de cómo se colocó la cámara a cierta hora y espacio y de cómo se tomaron decisiones por alguien con un interés propuesto, como vender un producto o lucir bien en cámara. Al mismo tiempo, no es sólo analítico o deconstructivista, sino también sintético, porque una nueva relación nace. No es ya más 1+1=2, sino 1+1=3. La nueva síntesis te otorga una suma que es mayor que las partes. Esto ocurre cuando uno añade un sonido o un texto a una imagen que no le pertenece. Volviendo a este proceso dialéctico y a Vertov y Eisenstein como antecedentes, esto sería un argumento que se presenta, no una reproducción de la realidad. No sería el "mira esta gente pobre y hambrienta. ¿Y ahora qué?", lo cual es un poco lo que es el documental, voyeurístico. Ahora sería el "¿cómo llegó a ser hambrienta, en primer lugar, y qué ha hecho desde que está hambrienta?". Este tipo de preguntas no son realmente respondidas por ciertos filmes, que sólo muestran o exponen, los llamados documentales expositivos. Lo que yo trato es de hacer preguntas, ser mas crítico o especulativo, trato de ver las relaciones entre la política y sus representaciones, la política de las imágenes».

Rafael Ricoy, en "Spectres of the Spectrum. La guerra electromagnética", en marzo de 2007, escribió:Realizada por Craig Baldwin en 2001, "Spectres of the Spectrum" es un feliz experimento en el que la narración está construida casi en su totalidad por fragmentos de materiales fílmicos de diversa procedencia, kinescopados de programas científicos de los 50/60, anuncios, material educativo, peliculas comerciales, documentales varios... Con todo este arrebatador material, Baldwin teje una trama (algo confusa y a veces demasiado sumisa al material disponible) en la que narra la lucha cruenta acaecida en los siglos XX y XXI (y lo que nos queda) por el control de los "media". Evidentemente para que todo encaje hay que usar el método paranoico (paranoico-crítico o conspiranoico según se mire) y en ocasiones la voz en off parece estar leyendo pasajes de alguna obra de William Burroughs. Particularmente terrorífico es el plano en el que aparece Bill Gates trazando una enorme © en una pizarra, en el contexto de la película parecería que este señor es el dueño de una maléfica corporación que quiere apoderarse del planeta

La banda sonora es excelente, incluye feroces activistas de la guerrilla sonora como Atari Teenage Riot, tempranos experimentalistas como Morton Subotnik o dulces retrofuturistas como Stereolab.

Craig Baldwin interviewed by Alvin Lu of Bay Guardian (1999), en Situationist 99, escribió:> I wanted to talk to you about the writing aspect. A lot of the energy in Spectres of the Spectrum is verbal. How does writing work in your films? Do you think of yourself as a writer primarily?

Filmmakers are driven to develop strategies to get information across. Like Eisenstein said, the ideal development of the motion picture form would be to be able to film Marx's German ideology, in other words to capture abstract/philosophical ideas, to develop a form of cinematic language as sophisticated and nuanced as verbal language. When you see a visual image, it's already there. It affirms itself. It doesn't have the ability to make inquiries or critique. So I'd like to - of course it's just a goal - develop this kind of sophistication of the visual lexicon to create the same kind of subtlety of nuance as writing or speech: with inflections, tenses, genders, subjunctive modes, interrogative modes. But, in the absence of that, what I'm trying to do is establish a kind of hybrid form of filmmaking.

> From your research, what you're presenting here is a sort of an unofficial history, but it comes from official sources, I take it.

OK, good question. It's not unofficial or official. The whole thing really has to do with the slippage between fact and fiction. Most compilation documentaries don't use fictional film. They'll use the archive film. They'll have a lot of the shots that I have, but they'll stop short of putting in some Japanese demon in there …

> All the stuff on Farnsworth and Sarnoff is true, though.

It's true. But I'm not quibbling whether Tesla did this in 1912 or 1913. That's minor. I'm interested in a pattern of co-optation of creative genius by corporations. It's a speculative history, considered in the tradition of science fiction. Science fiction is a kind of history. It's the speculative history of the future.

> Is it too simplistic to say (as the film says at certain points when you make specific comparisons between Gates and Sarnoff) that current technophilia is some kind of replay?

Gates is different from Sarnoff in a million ways. But for once just put them next to each other and consider it. My portrait links the boosterism of technological progress of the 1990s to the 1950s, which was a very similar postwar period, a time when there was this naive, unconditional belief that technology will make everybody's life better. The simultaneous juxtaposition of two perspectives - I call this "parallax viewing." One can see (historical) depth through a kind of stereoscopic vision, by viewing the pattern emerging in two time periods - the 1990s and the 1950s.

> Is collage, beyond just being a form, a means to address these issues?

For me there's a perverse justification to use the throwaway detritus, the waste of postindustrial Hollywood. This neotribal scavenging through the crumbs on the table to bricolage something beautiful, patchwork, made up with incredible diversity, variety, and changes of texture - is an authentic response from the margin. But it also has the element of critique, which is more trenchant because it uses the images against themselves.

Craig Baldwin interviewed by Transmission Films, en Spectres of the Spectrum and Sonic Outlaws, escribió:> Sonic Outlaws addresses issues like "fair use" and "free airwaves" long before issues now linked to the Internet like "open source" and "file sharing." Is the resonance surprising to you, or not?

No, the resonance between the themes in "Sonic" and the "open source" movement do not at all surprise me, because in fact the central theme in "Sonic" is 'media democracy"--tracing the struggle between the forces that want to use community technology for the free dissemination of ideas against those that see the media platforms as a road to profit. That is more or less explicitly stated in one of the interviews (Erik Davis'). This battle has been going on for, well, centuries, and will continue for centuries, regardless of the media at hand--print, telegraph, radio, television, and now the Internet. What's sharpened the contradictions now is that we are at a historical moment where the democratization could be finally realized, what with cheap phones and computers and Xeroxes and Super 8 film, and video…but perversely, we are seeing a very aggressive privatization/litigious climate along the corporate holders of intellectual property rights. It is this tension that my movie is driven by.

> Spectres of the Spectrum hints that technology has gone awry. Do you believe it has? What's your prognosis for the next decade? And beyond?

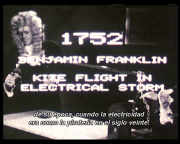

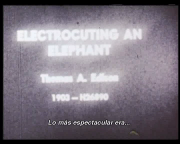

Well, "S.o.S." is pessimistic, that's for sure, but that shouldn't be oversimplified into some blanket disavowal of technology. In fact, the film celebrates technological innovation--pioneers like Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Graham Bell, Nikola Tesla, and Philo T. Farnsworth--for their visionary abilities. It understands their inventions as artistry--the design for the alternating-current generator came to Tesla in a flash, while the sun was setting in Budapest, whilst reciting a poem by Goethe! It was more of the insight of a poet or a visual artist with a very vivid imagination, than it was the result of thousands of hours of trial and error, conducted by hired workers, that characterized the developments of Edison. He was the pragmatist, as was Sarnoff, while my film valorizes their respective muses Tesla and Farnsworth. As a child of the twentieth century, I must acknowledge the contributions that their machines have made to the quality of life...so it is not the tech itself that is "evil" or flawed, but it is the human application! Tesla dreamt of free energy for all by tapping into natural energy sources like the ionosphere. This is of course the communist dream--socialism plus electricity! But their patents were stolen and the corporations consolidated more and more power, turning the tools into siphons for draining wealth from the consumers to the owners (witness the current corporate scandals), and ultimately towards war (Sarnoff/G.E.'s production of nuclear weaponry). As to a prognosis for the future, my answer would be similar--just as there are no "essentially" evil technologies, just their applications, there is no immanent, foregone future scenario, pre-fabricated and waiting to materialize.

> Are your films more about cultural criticism or subversive fun?

Of course the distinction between 'cultural criticism" and 'subversive fun" is a totally artificial one, a product of a guilt-ridden Calvinist political philosophy that went out with Dada, doncha know? Who was it that said "you can't fight alienation with alienated means"? And remember Emma Goldman's adage "I don't want a revolution that I can't dance to" [sic]. The Surrealists, the Situationists, the Yippies, the feminist movement and the punk rebellion have all taught us that the personal is political and the revolt of desire is an absolutely necessary plank in any political platform. My work educates as it entertains, understands humor and laughing as instruments for literally shaking up the status quo of the body... back to Wilhelm Reich! Ha! I realize that your bi-polar categorization can be a useful way of apprehending a media-artwork, through rhetorical opposition, a dialectic, so to speak, but why stop at two? My work--well, any work--can be "read" through any number of "critical matrices", and each reading is just as "true" as the other. The question remains then, through which film-critical lens do we choose to interpret the meaning of a work? When the audience starts asking itself these questions, well then, I have succeeded in pointing out the arbitrariness of cultural tastes and the ways in which meanings are linguistic constructions. Of course the found-footage goes a long way in that direction too.

> In a post-Napster world, what are your feelings about piracy?

The Piracy question. Of course "piracy" is an(other) very rich and problematic term, meaning different things to different people, generally depending on where they are in the intellectual-property pecking-order. What I and Negativland and Emergency Broadcast Network, et alia advocate for in "Sonic Outlaws" is not "bootlegging"--the complete wholecloth lifting of another's creative work, so to re-direct his/her potential revenue stream into our coffers. Of course, this is the legalistic sense of the term. I choose to rather aggressively embrace the fantasy elements of the character, and cast it in the romantic South Seas to boot. Picture a sailor, a poor sailor, whose boat has gone down, and he's gasping for air among the watery peaks, and he manages to grab onto a floating spar. He grapples his way onto the top side of it, from which prospect he is better able to shout out his calls for help. Do you think that our poor mariner should agonize over whether that spar came from his craft or another's? Now let's take the allegory a step farther...let's say he's able to reach a desert shore, and with natural vines and a whole lotta invention (daughter of necessity, after all) he ties a bunch of beached spars together and fashions a sea-faring vessel, in the crude image of a luxury liner...in fact the luxury liner that originally steamed over his fishing boat. I would say that was pretty ingenious, and his savage satire a testament to human resilience and courage. I call my own films the products of a post-industrial cargo-cult. Now that his vessel is seaworthy, you better be careful who you call pirate, you arrogant neo-colonial tourist who have turned my fishing inlet into a bogus tiki-bar resort!

Ficha técnica

- Guion: Craig Baldwin.

Fotografía: Bill Daniel (B&W).

Productor: Craig Baldwin.

Reparto: Sean Kilkoyne, Caroline Koebel, Beth Lisick.

DVDRip VOS - AVI (Copia con subtítulos incrustados publicada en Terrorfantástico...)

detalles técnicos u otros: mostrar contenido

detalles técnicos u otros: mostrar contenido

Spectres Of The Spectrum (V.O.Subt)[Alimaña][Terrorfantástico].avi [872.48 Mb]

Spectres Of The Spectrum (V.O.Subt)[Alimaña][Terrorfantástico].avi [872.48 Mb]